Visceral Fat, Pre Diabetes and Type 2 Diabetes!

The Connection Between Visceral Fat, Pre diabetes and Type 2 Diabetes!

Type 2 diabetes does not appear suddenly.

It develops gradually — often over years — and visceral fat is at the centre of this process.

Understanding this connection is critical.

What Is Visceral Fat?

Visceral fat is the fat stored deep inside the abdomen, around the liver, pancreas and intestines.

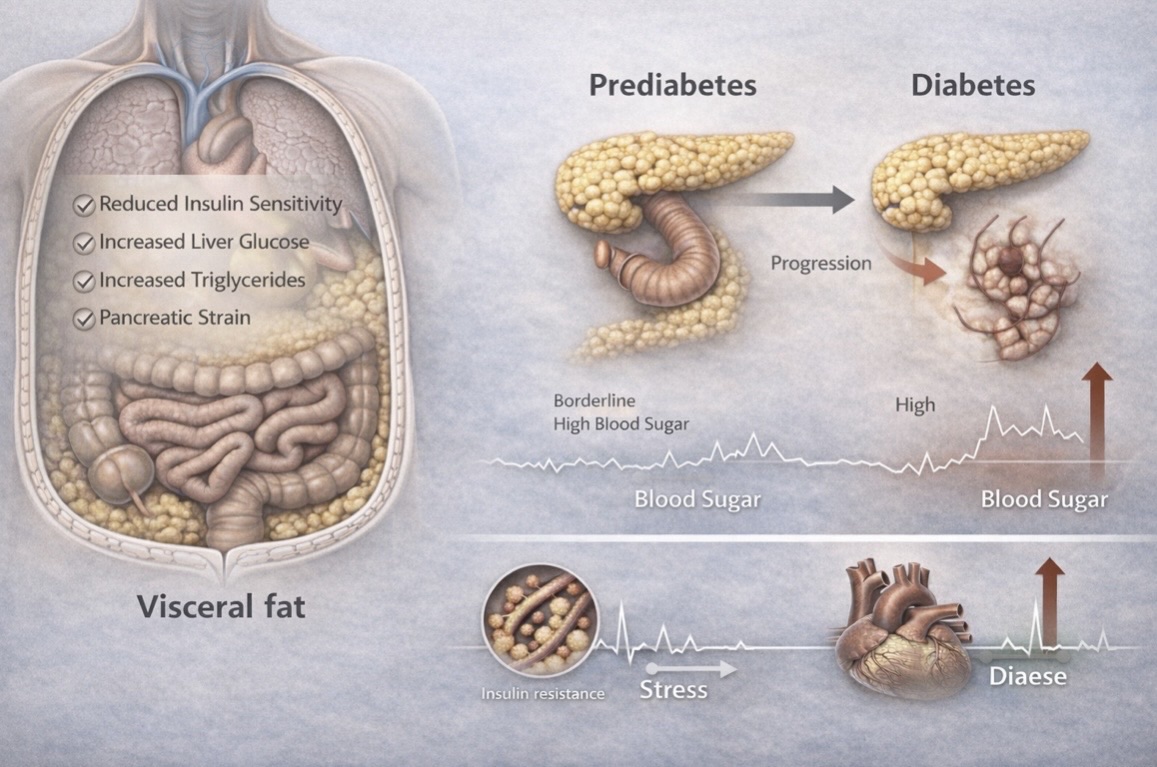

Unlike the fat beneath the skin, visceral fat is metabolically active. It releases inflammatory substances and hormonal signals directly into the liver, promoting:

Insulin resistance

Increased glucose production

Higher triglycerides

Fatty liver

Systemic inflammation

It is not passive storage fat — it actively drives metabolic disease.

How It leads to pre diabetes:

When visceral fat increases, the liver and muscles become resistant to insulin, meaning their cells need more insulin to be able to absorb glucose from the bloodstream.

The pancreas compensates by producing more insulin. For a time, blood sugar remains only mildly elevated. This stage is called pre diabetes.

Common early signs include:

Borderline fasting glucose

HbA1c in the pre diabetic range

Rising triglycerides

Increasing waist circumference

Most individuals feel completely well.

But internally, pancreatic beta cells which produce insulin are under strain.

If visceral fat continues to accumulate, compensation fails — and pre diabetes progresses to type 2 diabetes.

Why South Asians Are at Higher Risk

South Asians tend to develop visceral fat at lower Body Mass Index (BMI) levels.

A person may appear “normal weight” yet carry significant abdominal fat and insulin resistance.

Waist circumference is often a better indicator of risk:

Men: Above 90 cm

Women: Above 80 cm

It is not just how much you weigh — but where fat is stored that is important.

The Self-Perpetuating Cycle:

Greater the visceral fat, greater the insulin resistance,

Greater the insulin levels, greater the storage of visceral fat.

Chronic stress, inactivity, refined carbohydrates and poor sleep accelerate this cycle.

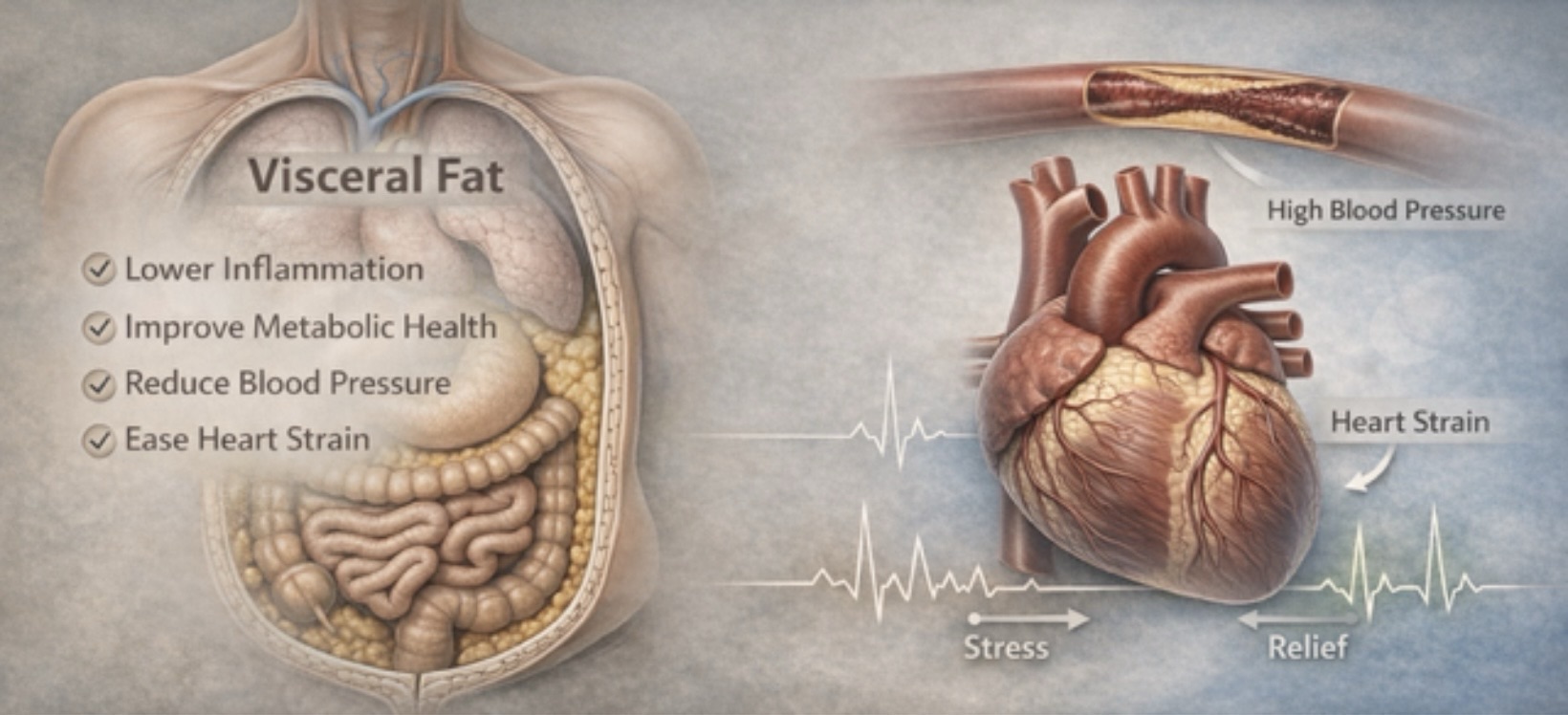

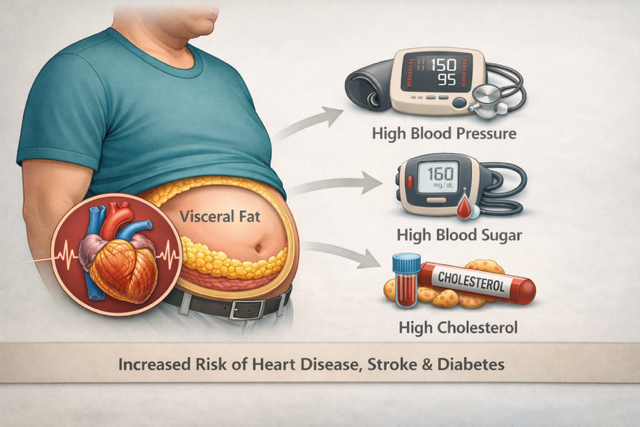

Over time, this leads to:

Persistent high blood sugar

High triglycerides

Low HDL cholesterol

Fatty liver

Hypertension

This cluster forms the basis of metabolic syndrome — with visceral fat as the driver.

The Encouraging Reality

Visceral fat responds well to lifestyle intervention.

Even a 5–7% reduction in body weight can significantly improve insulin sensitivity.

Effective measures include:

Regular brisk walking

Resistance training

Reducing refined carbohydrates

Adequate protein intake

Good sleep

Stress management

When addressed early, pre diabetes can often be reversed.

Summary

Visceral fat is the main driver of insulin resistance.

Pre diabetes is a warning stage, not a harmless condition.

South Asians are vulnerable even at lower BMI levels.

Waist circumference is a powerful risk marker.

Early lifestyle correction can prevent or delay type 2 diabetes.

Abdominal obesity is not merely cosmetic.

It is a metabolic warning sign.

Related article:

‘Waist Size, Blood Pressure, Blood Sugar And Heart Health!’.